Book Review by Carol Khoury

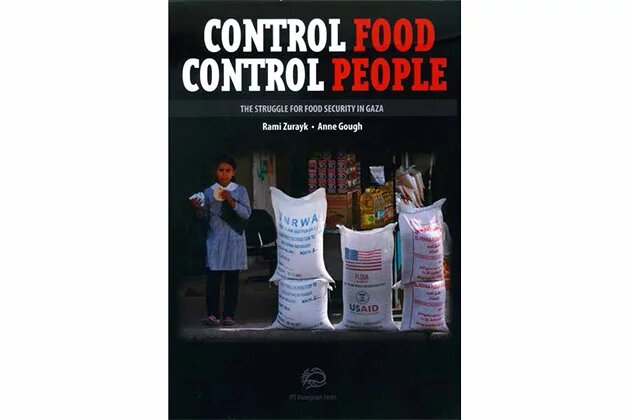

Zurayk, Rami & Gough, Anne. Control Food Control People: The Struggle for Food Security in Gaza. Institute for Palestine Studies, USA, 2013. 47 pages, with photos, maps, graphs, and appendices (total 70 pages).

While the title of the book references Henry Kissinger's remark ‘who controls the food supply controls the people; who controls the energy can control whole continents; who controls money can control the world’ the devastating reality in Gaza demonstrates a yet more tragic allusion to the saying ‘Qu'ils mangent de la brioche [let them eat cake]’. Palestinians in Gaza are starving because, inter alia, they cannot grow their own food, so, they grow and export carnations! Why? Rami Zurayk and Anne Gough chronicle the ultimate dystopia of the real version of the hunger game(s). In answering the question ‘why’, they go on to answer the more important questions of ‘how’, ‘for whose benefit’, and ‘by whom’.

From the outset, with no introduction yet in a very apt manner, Zurayk and Gough skilfully manage to make the reader feel, from as early as the second page, the omnipresent hunger in Gaza. The book comprehensively examines the nexus of people, land, and food security in Gaza. Referencing theoretical approaches of thinkers like Henry Kissinger, Sara Roy, Patrick Wolf, and Samir Amin, the book uses food regime theory's analysis of the power dynamics on food and farming systems to illustrate how Israeli economic policies replicate the corporate food regime in its dominance and dependency creation in Palestine, particularly in Gaza. It also incorporates the concept of the purposeful destruction of agency and food security highlighted by the theory of 'de-peasantization’, framing it as a strategic tool of colonial practices. In effect, Gaza has become an extreme example of the rupture between the global corporate food regime and food security.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) confirms that ‘since the onset of the Israeli occupation in 1967, the economy of the WBGS [West Bank and Gaza Strip] has been an "income economy" rather than a "production economy" – making the WBGS extremely vulnerable to the Israeli labour and goods market’ (p. 34).

Palestinians in general are often cast as powerless victims, with the West Bank and Gaza Strip serving as theoretical containers in which activities are studied and policy prescriptions are made, but over which the Israeli occupation ultimately retains absolute control. In reality, people in Palestine make individual decisions every day, but the ability of Palestinian communities to make collective decisions about their food and farming systems is curtailed by the occupation (p. 32). Israeli occupation has used food insecurity as a weapon in its colonial project in Palestine in much the same way that, in the global food regime, the economic centre uses it against the periphery.

While Israeli regimes have framed Palestinian food insecurity as an unfortunate by-product of the conflict, the international community in its refusal to politicise aid, has contributed to the legitimatisation of this view of the conflict (p. 47). Although the tunnels are a direct response to Israeli economic and territorial strangulation, international aid agencies refuse to purchase materials they suspect have been made using elements imported through them. When funding new water infrastructure projects, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) like Oxfam or government agencies such as the European Commission's Humanitarian Office, will not purchase from the only remaining pipe factory in Gaza because of the suspicion that it obtains necessary materials from the tunnel trade (p. 37). As a matter of fact, international aid projects in Gaza have been largely delegitimised by their deference to Israeli food insecurity strategies. When food aid is devoid of ecological, historical, and political context, it cannot fill the vacuum created when food insecurity damages food culture.

Not only the international donor community, but also the Palestinian Authority, has encouraged the shift towards abandoning agriculture. If the Palestinian Reform and Development Plan (2008) is fully implemented, Palestine will become a net food importer, subject to the whims of its major trading partners: Israeli businesses (p. 30). As long as Palestinian policymakers, and the international donor community, do not work to keep farmers on their land (rather than adopting policies that do the opposite), both are rendered complicit in Israel's war on the Palestinian agricultural sector.

Utilising an impressive and relevant lexicon, the authors proficiently embroider a contemptible canvas of all sorts of hunger: for food, for food security, for food sovereignty. The main conclusion of the book, however, is a promising one. Deploying terminology as its threads (food sovereignty, chronic food insecurity, food vulnerability, entitlement to food, metabolic rift, nutritional transition, humanitarian minimum, community agency, resistance economy, hydro-hegemony, and many more) the central motif of the book is to recast the definition of food security. Indeed, the authors propose an expanded definition informed by two complementary critical discourses: global food regime theory, and the political economy of occupation (p. 5).

If all people are entitled to food security, they must also be entitled to participate in how food security is defined and measured (p. 16). In actuality, food sovereignty should be considered a prerequisite for food security. When the authors used food sovereignty as the foundation for their redefinition, they applied entitlement theory's concept that food insecurity is not caused by unemployment and low income alone. Instead, they argued, rightly, that it is a result of structural inequities in the food and farming systems that extend to social relations, employment, and trade relations. Their proposed definition focuses on particular determinants of food security that have been methodically impaired in order to serve Israeli political, economic, and territorial objectives.

Food security exists when all people with full agency and freedom from fear of not having enough to eat have, at all times, physical and economic access to healthy farming systems and means of land reform. All people should be/ are entitled to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food made possible through the support of agrarian livelihoods. All people are able to meet their dietary needs and preferences for an active and healthy food culture. All people should be able to meet these determinants through mechanisms of democratic deliberation. (p. 18)

The recast definition of food security that the authors are lobbying for is based on the components they found to be missing from the conventional definition, namely: access to resource entitlements, agrarian livelihoods, community agency, and a local food culture. This approach links people to the food they consume, accounts for the political framework in which food security actions are deployed, and transforms the notion of food as a commodity to food as an entitlement (p.18).

While conventional food security definitions have always avoided any reference to the spatial political control of food systems; food sovereignty, on the other hand, recognises class and power dynamics not as issues of charity or development, but as necessary targets of democratic change in any attempt to challenge the prevailing corporate food regime.

No less important than the recast definition, the book also contains two recommendations: the urgency of redefining food security and linking the Gaza Strip to food movements around the globe (p.43); and the importance of revalorising Gaza's vulnerable food-producing economy, not only to ensure food security, but also as a strategy of resistance (p. 41).

The situation in Gaza confirmed the authors' thesis that food insecurity is not a side effect of the occupation, but rather a strategic goal pursued by all Israeli governments, a strategy that not only prolongs public health and environmental disasters, but also ensures that no long-term development or autonomy is possible in Gaza (p. 43). While it is possible that the end of the siege could marginally improve selected food security indicators, it is unlikely to improve the state of Gaza's agricultural system or levels of chronic food insecurity. Gaza would not only remain occupied, but also still be surrounded by countries, donors, and agencies more concerned with maintaining their own presence in Palestine than with ending the occupation (p. 47).

While the whole world watched, and is still watching, Gaza slipped from being a food exporter (as late as 1967), to having eighty-eight percent of its population receiving food aid (in 2011). The situation on the ground is set to worsen, in tandem with the pace of failing international integrity. If ‘humanitarian minimum’ is now trusted to be the accepted bottom, the world might be only two steps away from a new disaster.

References

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (2007) Comprehensive food security and vulnerability analysis for the West Bank and Gaza Strip (CFSVA) – Report. Available at http://www.fao.org/economic/esa/publications/details/en/c/122659/ (accessed 1 August 2017).